Understanding the Court Process

There are a number of different court meetings, hearings, and trials that you will hear about as a foster parent. The most typical outcome of any particular day your child’s case is discussed or heard within the court system is…. Nothing.

Most court dates are either check-ins for the court to briefly hear the status of the case (e.g., child is still in care, parents are engaged in services and visiting regularly). Much of the time, hearings or conferences are continued for a variety of reasons (e.g., the court is too busy that day, not all attorneys are able to be present, an attorney has filed a motion for a continuance, etc.). Given how overwhelmed children’s attorneys are, it is not uncommon to hear from them only when there is a court date coming up, since they need to report to the judge that they met with their client. Hearing from an attorney that they need to make a visit to meet with you because there’s a court date coming up does not mean there is anything wrong, or that there is any imminent change in the case. This is a point we can’t emphasize enough because novice foster parents often worry about this, and will reach out to us in despair upon hearing from an attorney in anticipation of court. We promise the vast majority of court dates involving your foster child have no immediate impact on your child’s placement with you. However, there are some times when key decision points occur within the court system, and it behooves you to understand the difference between different types of court dates.

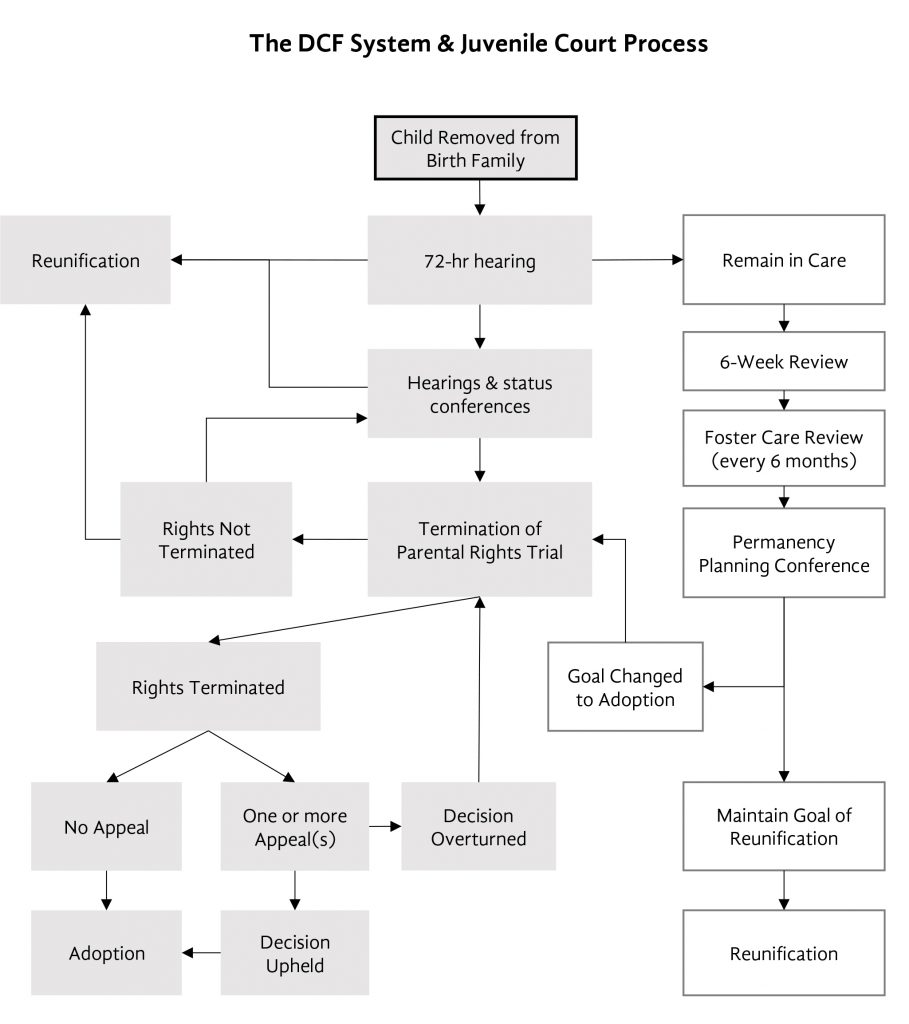

Temporary Custody Hearing/72-Hour Hearing

Although DCF has the immediate authority to remove a child from his/her birth family if the child is in immediate danger, a judge must approve the removal. In theory, a hearing to determine whether the removal was warranted is supposed to be held within three days of a child coming into foster care (hence “72-Hour Hearing”). In practice, however, it may take much longer due to a shortage of lawyers for parents and children, and an overwhelmed court system. It may also stretch out over multiple days and those days might not be consecutive. Birth parents can also waive the hearing and not object to their children’s placement in foster care (though this is more rare).

If a judge determines the removal was not warranted, he or she can order that custody be returned to the birth family immediately. It’s a good idea to know when the 72-hour hearing is scheduled, so you can have some forewarning of the possibility of immediate reunification. If the ruling is that the child should remain in care, you might never hear about the 72-hour hearing unless you ask.

Permanency Hearing

These hearings are also basically a check-in for the Court. They are required by statute, and occur on a calendar set by the statute, the timeline for which has nothing to do with the actual progress of the case. For most children, these are an extremely unimportant event. This is different for teens, who are invited to participate in their own permanency hearings. For them, that can sometimes be helpful and empowering. Often, judges will come sit at a table with them, their lawyer, DCF’s lawyer and the parents’ lawyer(s) and discuss with the teenagers their own plans for their future.

Pre-Trial Conferences

These are essentially dates at which the Court checks in to try to ascertain the status and likely direction of the case, and to set future dates. For example, if a case is approaching the need for a termination of parental rights trial, then the court will set dates for that while all parties are in attendance. In Western Massachusetts, you’ll hear about pre-trial A and B – these are both pretrial conferences, and the terminology isn’t used elsewhere in the state.

Termination of Parental Rights Trial (TPR)

At the point when DCF determines that reunification is not possible, and it is in the best interests of the child to terminate their birth parents’ rights, a date is set for a Termination of Parental Rights (TPR) trial. “A date” is actually misleading because typically numerous dates are scheduled, and they might not be dates in succession. For example, the first dates for trial might be June 6th and 7th, with the third and fourth dates set for August 12th and August 20th. It really depends on the availability of the court. Rarely do trials last only one day, and they are often heard sporadically over a series of weeks, or even months. Depending on the complexity of the case, the number of children and fathers involved (cases center around a single birth mother, so there is only one), and the length of time the children have been in care, a full trial can be a lengthy proposition with numerous witnesses.

However, just because a trial is scheduled doesn’t mean a trial will actually go forth as planned. As mentioned previously, trial dates can be continued repeatedly, and sometimes a trial will end up not being necessary for the case to come to a resolution.

If a trial does proceed to its completion, the Court does several things: it makes a finding that the parent does or does not continue to be “unfit,” meaning unable to provide care and custody of the child now, or at a time reasonably near (with “reasonable” measured by the life of the child). It determines whether the child continues to be “in need of care and protection.” Typically, if the parent remains unfit, the child continues to be in need of care and protection. If the Court determines that a parent remains unfit, and that a child continues to be in need of care and protection, the Court will then consider whether to terminate parental rights.

There are many factors the Court must consider to make that determination (fourteen are written into the statute), but they boil down to:

- Is the parent likely to stay unfit for more time than we should make the child wait for the parent to make progress?

- Is it generally in the child’s best interests for the parents’ rights to be terminated?

After entering a termination decree, the Court has the right to order post-termination and/or post-adoption contact, but does not have to and often will not. After termination, the parent may choose to exercise his or her appeal rights.In the unusual event that a Court finds the parent unfit and the child in need of care and protection, but does not terminate, the child is then committed to the permanent custody of the department. This might happen for an older child who has expressed a wish not to be adopted and not to be legally severed from a parent. It preserves a backup plan for a child with no intended adoptive placement; in the unlikely event that the parent does become fit, the child can be reunified.

The Appeals Process

An appeal is the biological parent’s effort to overturn the Court’s decision, typically on termination of parental rights. The appeal is usually heard by a single justice or panel at the Appeals Court, which is the middle tier of the court system in Massachusetts. You can reasonably expect an appeal to add at least year to a case. Technically a biological parent has thirty days after a decision to file for an appeal, but it is far from unheard of for them to be allowed late, so you should not be surprised if that occurs. You can attend the hearing on the appeal (which will almost always be in Boston). The findings from the appeal are published, but pseudonyms are used, so your child will not be identifiable. Appeals are extremely hard for biological parents to win. Technically, there is the option for further appeal to the Supreme Judicial Court (highest court in the state) after the Appeals Court, but it is rarely exercised/allowed.

In the event that an appeal is successful for a birth parent, he or she does not automatically get a different verdict in the case. Rather, a new trial is ordered. This second trial may or may not come to a different conclusion and decision than the first.

Other Terms, Trials, and Hearings

Prima facie trial / “prima facie”

This trial is conducted when a parent has not been involved. Often, this will involve a putative father (a man whose legal relationship to a child has not been established). Basically, DCF presents one or two witnesses to the court, reports on the parent’s lack of involvement and their efforts to engage the parent. The Court then terminates the parent’s rights (or cuts off the opportunity for them to establish rights in the case of a putative father) after the very brief presentation. After that, the attorney for that parent will no longer be a part of the case.

Third-party custody hearing

This is a hearing to determine if the Court will award custody to a particular person. Often, this person has sought to be a foster placement through DCF and DCF has refused. Third-party custody may be sought when a potential foster parent, such as a relative, has been refused by DCF as a kinship foster placement (for reasons ranging from the serious to the trivial). What the third party then does is ask the court to place the child directly with the third party, rather than through DCF as a foster placement. The court has more leeway to place a child with a third party despite that person not meeting DCF guidelines (e.g., a criminal record in the distant past, not enough space in their home, etc.). Third-party custody will typically be addressed in a hearing apart from a trial, though it is possible for the issues to be merged.

Guardianship

Guardianship is a potential permanency option for a child that does not require termination of parental rights, as adoption does, and does not create the same legal relationship adoption creates. It is an option often considered for older children unwilling to consent to adoption and opposed to having their parents’ rights terminated, even if they can’t live with those parents.

Want to learn more about navigating your role as a foster parent in Massachusetts?

It Takes a Village is the first and only comprehensive guidebook available. Order your copy today!