An Overview of Foster Care and Adoption in Massachusetts

Child abuse and neglect is a serious social welfare problem that affects every community in our nation.

At AOK, we believe that, as a society, we have a collective responsibility to keep children safe from harm.

When a child is being neglected or abused, the State has the authority to remove that child from their home and temporarily place that child in a safe home with a foster family. In addition to serious bodily harm and emotional abuse, neglect and abuse also include: allowing a child to live in unhealthy or dirty living conditions; living without proper food, clothing, heat, or medical care; failing to require a child under the age of 16 to attend school; or allowing a child to see or hear domestic violence.

DCF and the Foster Care System

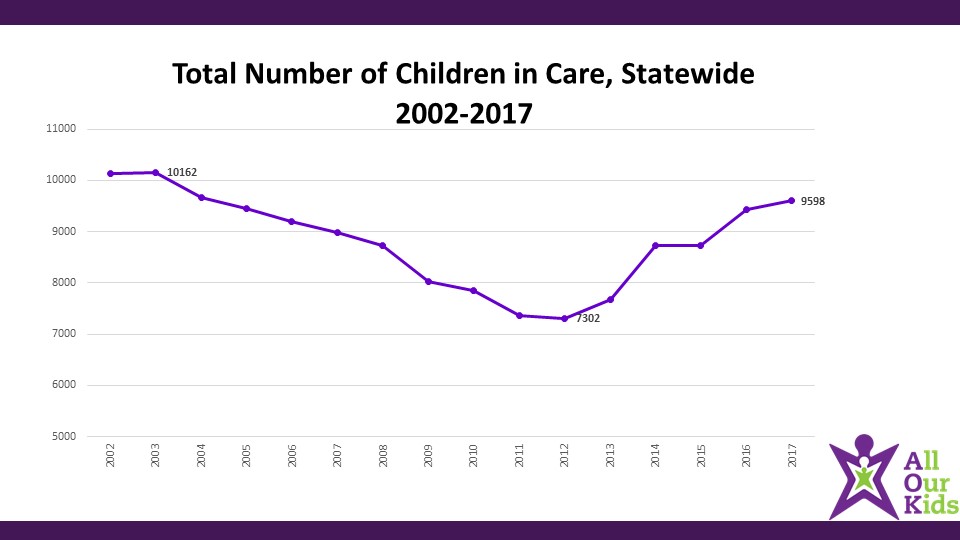

In Massachusetts, the Department of Children and Families (DCF) is the state agency tasked with ensuring the safety and well-being of our most vulnerable citizens: our children. Although the DCF central office is located in Boston, there are area offices throughout the state. In the Western region, DCF offices are located in Springfield, Holyoke, Greenfield, and Pittsfield. Over the last fifteen years, the number of children in foster care statewide has fluctuated from a high of 10,162 (in 2003), to a low of 7,302 (in 2012). As of last September (2017), there are 9,598 children in care across the Commonwealth.

Placements

Whenever possible, DCF attempts to place children in foster care with a biological relative (a “kinship” placement). This might be an aunt, uncle, grandparent, or other relative. If such a placement is not possible, if a child has a sibling in foster care or who has been adopted through foster care, DCF will attempt to place that child with that sibling. Alternately, a child may be in a “child-specific” placement, where a child is placed with a teacher or other adult in their life with whom they’ve already had a pre-existing relationship. When none of these options are viable, a child is placed in a non-relative home with foster parents who have no pre-existing ties to the child, either through biological or other relationships, or through parenting of that child’s biological sibling.

The Birth Family

The main goal of the foster care system is to strengthen the child’s family of origin so that the child can be reunified with that family. While their children are in foster care, birth parents are required to engage in services that address the reasons that warranted removal of their child. These services often include counseling, obtaining adequate housing, parenting education, and abstinence from substance use.

While their children are in foster care, birth parents (and birth grandparents) also have the right to visit their child, as long as they do not pose a threat to the child. These visits are typically weekly, and take place in DCF offices. Although each child in foster care is assigned a social worker, that social worker is primarily responsible for working with the family of origin to help the family access needed services and monitor progress. The role of foster parents is crucial in this work, ensuring that the child’s needs are met while they are in foster care. In addition to basic needs such as food and shelter, these needs are emotional, educational, medical, and social. Just like all parents, foster parents are these children’s best and most important advocates.

Permanency

The work of strengthening a family doesn’t happen quickly, and this is part of the reason children can be in foster care for a long time before they are reunified with their family of origin, or adopted by another family (sometimes the foster family they have already been with). Although federal guidelines suggest that children should achieve permanency (reunification, adoption, etc.) within 24 months of the initial placement in foster care, such guidelines are almost impossible to follow given how overwhelmed our current foster care system is. Although some children are fortunate enough to achieve permanency in less than two years, most are in foster care for several years before achieving permanency.

The Juvenile Court

While a child is in foster care, DCF works actively and closely with the juvenile court system throughout the Commonwealth, because removing a child from their family of origin needs to be approved by a judge. The courts monitor the progress of the case, and can ultimately decide whether a child can be safely reunified or whether a different permanency plan needs to be enacted. This plan can include adoption or guardianship.

Adoption

During the time children are in foster care, their birth parents are given as much opportunity as possible to make the changes in their lives that are necessary to safely and effectively parent. If they are unable to do so, they have the option of voluntarily surrendering their parental rights and agreeing to have their children adopted. Alternately, the State will pursue a termination of parental rights trial, where a judge decides whether or not to terminate their rights. When rights are terminated, a child becomes “legally free” for adoption. If that child is already placed in a pre-adoptive foster home, that family then can proceed to legally adopt the child. If the child is not placed in a family willing and able to adopt them, an adoptive family is recruited for the child. Once a child is adopted, there is no additional oversight or monitoring from DCF (though post-adoption supports are available), and the legal relationship between adopted child and adoptive parent(s) is the same as that between a child and their birth parents.

The Current State of Foster Care in Massachusetts

The majority of children in foster care are placed with a relative or other known person (a "kinship or "child-specific" placement). But a large minority of children are placed into families whom they have never previously met ("unrestricted" placements). Although not all foster children are placed singly into a foster home (some are placed with one or more siblings who are also in foster care), the fact that 343 such homes are available for the 532 children who need them indicates a serious problem in our foster care system today: There are not enough homes to meet the needs of children in foster care.

What this means in practice is that children are not “matched” with the best home that is available.

In too many instances, children are placed in any home that has space for them, whether or not it is the best possible match for them. For instance, a child who would greatly benefit from the care and attention of being the youngest or only child in a home might be placed with other young children. Children might also not be able to stay in their home community and school if there is not an available foster home in that same community.

Short-term Placements

Additionally, a foster family might be willing to provide care on an emergency basis – maybe for a night, a weekend, or a week – but cannot make a long-term commitment to that child because of other responsibilities in their lives. In these instances, a child might be able to stay with a family for a very short period of time while DCF seeks a more permanent situation. But the next family who agrees to help might also not be a long-term possibility. This is how children in foster care bounce around from family to family. It isn’t often because their needs are so great that families keep passing them off. It’s because families overextend themselves on a short-term basis to help a child when other options aren’t available. But these families are often not able to continue to provide care in the long-term. The shortage of foster homes means that children suffer and are made to move unnecessarily. Such is the case for children of all ages – from newborns ready to be discharged from the hospital, to young adults who are aging out of the foster care system.

Adoption Through Foster Care

Families who are specifically interested in adopting a child through foster care are “pre-adoptive” foster parents to that child before an adoption is finalized, and go through the same approval, training, and licensure process as any other foster family. Although DCF does its best to match a pre-adoptive family with a child who has a higher likelihood of being adopted, unless parental rights have already been terminated, there is always a chance that child can be reunified with their birth family or with a biological relative. If a birth family has a history of services with DCF and has had parental rights terminated for other children in the past (especially if the reasons for prior termination have yet to be adequately addressed), DCF might be more inclined to place a child in a pre-adoptive home. All foster parents are given as much information about a child as possible prior to a placement, and they determine whether that particular child might be a good fit for their home and family.

Although pre-adoptive parents can understandably be eager for parental rights to be terminated and for their foster child(ren) to become free for adoption, it is important to understand that as foster parents (pre-adoptive or otherwise), part of our role is to support DCF’s mission to strengthen families and reunify children with their families of origin whenever possible. DCF is not an adoption agency, and not all children go on to be adopted. It is a good thing when a birth parent is able to make the necessary changes to engage in healthier behaviors and parent their children safely and appropriately. But when that cannot happen, children need families to make life-long commitments to them through adoption.

The Importance of Support

Being a foster or adoptive parent is a rewarding and enriching experience, but just like any parenting, it is not without its challenges. The foster care system can be bureaucratic and impersonal (just like any other state agency). And children who have been abused or neglected can have unique needs that are difficult to manage. (It is important to note, however, that children in foster care have a range of special needs, from mild to severe, and not all children involved in foster care have significant needs.) These challenges are a big part of why AOK was founded – to support foster families in this extraordinary work. We have found that when we are part of a community of individuals and families who look like ours, understand these unique challenges, and can provide support to each other, the challenges become easier to navigate. At AOK, we can be with you at every step of the way to offer information, provide resources, or lend support. We’re a community of parents who have been there and are eager to help. Don’t hesitate to reach out to us, whether you simply want to know more or are ready to start the process.

Interested in learning more?

It Takes a Village compiles and presents the information and support that families routinely seek from AOK, with empathy and wisdom.

This 87-page guide is what every foster parent needs on their bookshelf.

It Takes a Village can be purchased on a pay-what-you-can-afford basis. No one will be denied this incredible resource due to an inability to pay.